-

About Streets

- Introduction

- Defining Streets

-

Shaping Streets

- The Process of Shaping Streets

- Aligning with City and Regional Agendas

- Involving the Right Stakeholders

- Setting a Project Vision

- Communication and Engagement

- Costs and Budgets

- Phasing and Interim Strategies

- Coordination and Project Management

- Implementation and Materials

- Management

- Maintenance

- Institutionalizing Change

- Measuring and Evaluating Streets

-

Street Design Guidance

- Designing Streets for Great Cities

- Designing Streets for Place

-

Designing Streets for People

- Utilities and Infrastructure

- Operational and Management Strategies

- Design Controls

-

Street Transformations

- Streets

-

Intersections

- Intersection Design Strategies

- Intersection Analysis

- Intersection Redesign

- Mini Roundabout

- Small Raised Intersection

- Neighborhood Gateway Intersection

- Intersection of Two-Way and One-Way Streets

- Major Intersection: Reclaiming the Corners

- Major Intersection: Squaring the Circle

- Major Intersection: Cycle Protection

- Complex Intersection: Adding Public Plazas

- Complex Intersection: Improving Traffic Circles

- Complex Intersection: Increasing Permeability

- Resources

Global Street Design Guide

-

About Streets

- Introduction

- Defining Streets

-

Shaping Streets

Back Shaping Streets

- The Process of Shaping Streets

- Aligning with City and Regional Agendas

- Involving the Right Stakeholders

- Setting a Project Vision

- Communication and Engagement

- Costs and Budgets

- Phasing and Interim Strategies

- Coordination and Project Management

- Implementation and Materials

- Management

- Maintenance

- Institutionalizing Change

-

Measuring and Evaluating Streets

Back Measuring and Evaluating Streets

-

Street Design Guidance

-

Designing Streets for Great Cities

Back Designing Streets for Great Cities

-

Designing Streets for Place

Back Designing Streets for Place

-

Designing Streets for People

Back Designing Streets for People

- Comparing Street Users

- A Variety of Street Users

-

Designing for Pedestrians

Back Designing for Pedestrians

- Designing for Cyclists

-

Designing for Transit Riders

Back Designing for Transit Riders

- Overview

- Transit Networks

- Transit Toolbox

-

Transit Facilities

Back Transit Facilities

-

Transit Stops

Back Transit Stops

-

Additional Guidance

Back Additional Guidance

-

Designing for Motorists

Back Designing for Motorists

-

Designing for Freight and Service Operators

Back Designing for Freight and Service Operators

-

Designing for People Doing Business

Back Designing for People Doing Business

-

Utilities and Infrastructure

Back Utilities and Infrastructure

- Utilities

-

Green Infrastructure and Stormwater Management

Back Green Infrastructure and Stormwater Management

-

Lighting and Technology

Back Lighting and Technology

-

Operational and Management Strategies

Back Operational and Management Strategies

- Design Controls

-

Street Transformations

-

Streets

Back Streets

- Street Design Strategies

- Street Typologies

-

Pedestrian-Priority Spaces

Back Pedestrian-Priority Spaces

-

Pedestrian-Only Streets

Back Pedestrian-Only Streets

-

Laneways and Alleys

Back Laneways and Alleys

- Parklets

-

Pedestrian Plazas

Back Pedestrian Plazas

-

Pedestrian-Only Streets

-

Shared Streets

Back Shared Streets

-

Commercial Shared Streets

Back Commercial Shared Streets

-

Residential Shared Streets

Back Residential Shared Streets

-

Commercial Shared Streets

-

Neighborhood Streets

Back Neighborhood Streets

-

Residential Streets

Back Residential Streets

-

Neighborhood Main Streets

Back Neighborhood Main Streets

-

Residential Streets

-

Avenues and Boulevards

Back Avenues and Boulevards

-

Central One-Way Streets

Back Central One-Way Streets

-

Central Two-Way Streets

Back Central Two-Way Streets

- Transit Streets

-

Large Streets with Transit

Back Large Streets with Transit

- Grand Streets

-

Central One-Way Streets

-

Special Conditions

Back Special Conditions

-

Elevated Structure Improvement

Back Elevated Structure Improvement

-

Elevated Structure Removal

Back Elevated Structure Removal

-

Streets to Streams

Back Streets to Streams

-

Temporary Street Closures

Back Temporary Street Closures

-

Post-Industrial Revitalization

Back Post-Industrial Revitalization

-

Waterfront and Parkside Streets

Back Waterfront and Parkside Streets

-

Historic Streets

Back Historic Streets

-

Elevated Structure Improvement

-

Streets in Informal Areas

Back Streets in Informal Areas

-

Intersections

Back Intersections

- Intersection Design Strategies

- Intersection Analysis

- Intersection Redesign

- Mini Roundabout

- Small Raised Intersection

- Neighborhood Gateway Intersection

- Intersection of Two-Way and One-Way Streets

- Major Intersection: Reclaiming the Corners

- Major Intersection: Squaring the Circle

- Major Intersection: Cycle Protection

- Complex Intersection: Adding Public Plazas

- Complex Intersection: Improving Traffic Circles

- Complex Intersection: Increasing Permeability

- Resources

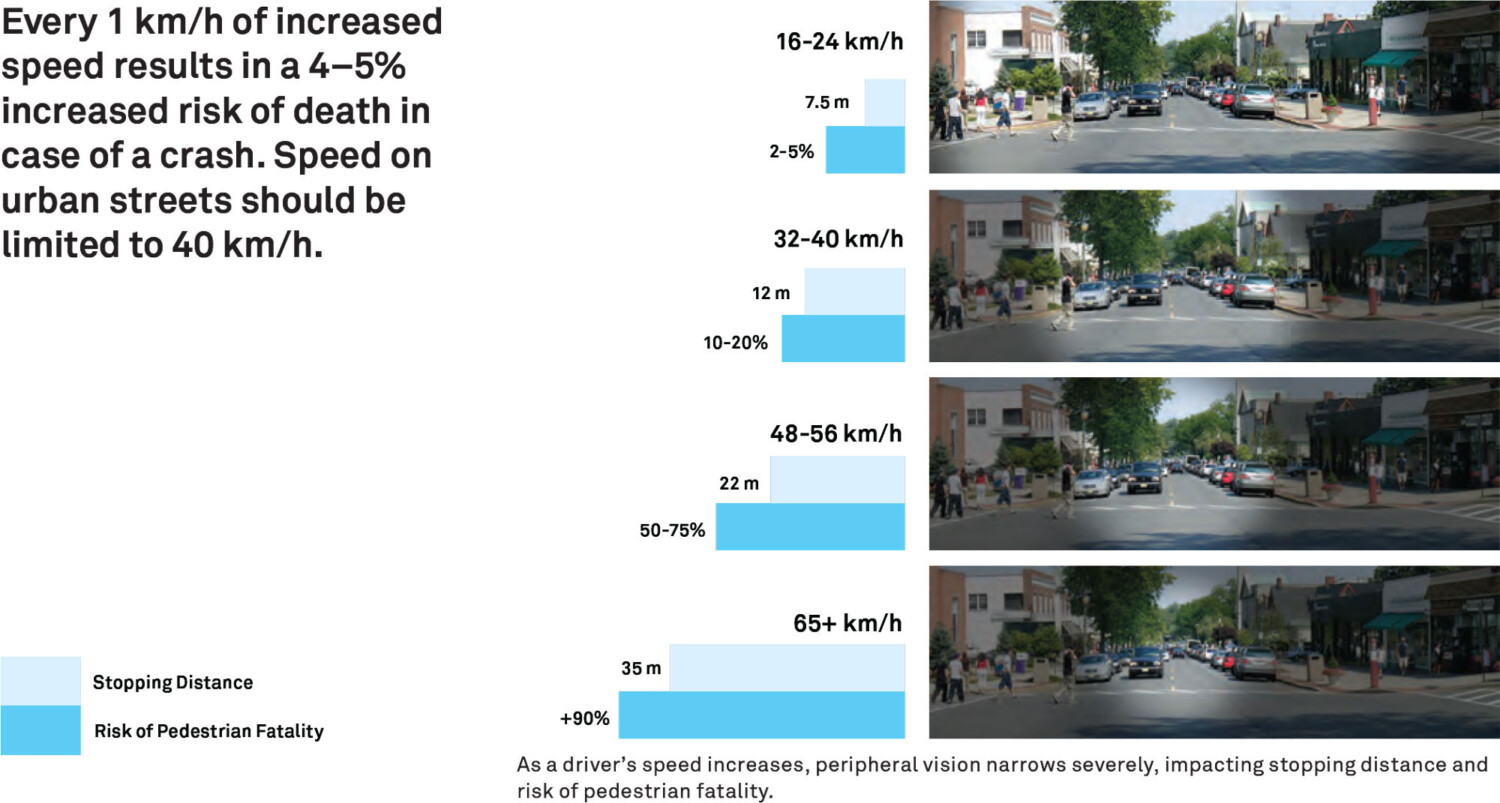

Design Speed

Design speed is the target speed at which drivers are intended to travel on a street, and not, as often misused, the maximum operating speed. Actively designing for target vehicle speeds is critical to safety. Changing a street’s design results in behavior changes. Practitioners must manage speeds by setting clear expectations for drivers. The level of walking, cycling, and activity, as well as the degree to which modes are mixed or separated, is the critical determinant of a safe vehicle speed. Reducing vehicle speeds opens up a range of design options that allow a street to function and feel like part of a city, rather than a highway. Designers must not use highwaybased design speed practices in urban areas. Instead, they must be proactive in limiting vehicle speeds, providing frequent pedestrian crossings, limiting the number and width of lanes, using low speeds for turn radii, and introducing trees and furnishings.

Conventional practice designates a design speed higher than the posted speed limit to accommodate driver errors. But, in fact, this practice only encourages speeding and increases the likelihood of traffic crashes, fatalities, and injuries.

A proactive approach selects a target speed and uses design to achieve that speed, guiding driver behavior through physical and perceptual cues. These cues include narrower lane widths and tighter curb radii, signal progressions, and other speed management techniques. Using lower design speeds in street design reduces vehicle speed and speed variation, providing safer places to walk, cycle, drive, and park.

The design speed for urban areas should not exceed 40km/h, with exceptions for specific corridors. To determine appropriate design speeds other than 40km/h, consider the multiple safety, health, mobility, economic, and environmental goals.

Speed, Severity, and Frequency

The most effective way to reduce fatalities and severe injuries on streets is to reduce vehicle speeds.1 The vast majority of people killed in traffic are struck on streets with high speeds, even though those streets represent only a small portion of a city’s total activity and movement.

Speed is the primary factor in crash severity and the likelihood of a crash occurring. Increased speeds result in longer reaction times, a narrower cone of vision,2 and increased stopping distances while providing less time for others to react. An increase in average speed of 1 km/h results in a 3% higher risk of a crash and a 4–5% increase in fatalities.3

Speed differential is also a critical component of safety. People walking or cycling are placed at great risk when faced with motor vehicles turning across their paths, at a speed much faster than their own. Keeping design speeds low on streets where cycles, cars, trucks, or buses share a lane or street reduces crash risk, and the likelihood of serious injury or death. A design assumption that modes are separate can become dangerous when user expectations vary. The safest streets match the degree of mixing with an expectation of mixing, using design to communicate the specific conditions.

Target Speeds and Context

Critical Guidance

Do not design streets for speeds higher than the posted limit.

Establish the target speed based on all users and not just drivers. Develop a realistic assessment of the way the street is used, and account for the immediate context and municipal safety goals. Design streets to constructively guide driver behavior, discouraging speeds above the target speed and promoting the safe mixing of multiple modes.

Set speed limits at the target speed if possible. If statutory speed limits are higher than safe urban speeds, set the design speed below the speed limit. Make speeding uncomfortable through design and operational techniques.

Target speeds must, in all circumstances and on all streets, allow people to walk along and to cross streets without substantial risk of being injured by vehicles. They must provide drivers with adequate time and distance to avoid striking pedestrians crossing the street.

Do not use target speeds of 60 km/h or higher. These speeds endanger safety on urban streets and are reserved for limited-access highways.

Recommended Guidance

Desired vehicle speed should be achieved by choosing street sections that encourage safe speeds. Keep the total number of through-traffic lanes to a minimum. Choose a small radius for turns, use signal timing to promote low speeds, and apply speed management techniques where the street section does not prove to be sufficient.

Where speeds greater than 40 km/h are allowed create a physical separation between vehicles and vulnerable users such as pedestrians and cyclists. Parked vehicles, built medians, buffers, or other vertical elements may be used as a barrier, though frequent opportunities for safe crossing must be provided. These should be ideally located at intervals of 80–100 m, and not more than 200 m. See: Speed Management.

Limit the speed differential within and between modes. If people walk in the same space as motorists, use a speed of 10–15 km/h. If pedestrians routinely cross the street mid-block, away from formal crossings, select a target speed of 20 km/h or less. If cyclists are mixed with motorists, but pedestrians do not share the same space, use a speed of 30 km/h or less, even at low traffic volumes. These speeds are also consistent with bus traffic.

Default design speeds based on street types or zones can be established as a starting point. Above 40 km/h, the use of specific engineering action, such as signalization and other conflict management techniques, is recommended to create basic conditions for safe use across all modes.

Urban streets can rarely accommodate pedestrians and cyclists safely when prevailing speeds are 60 km/h or higher. If speeds cannot be reduced, high-quality walking and cycle facilities should be provided at grade, with robust protection such as parallel parking, trees, and medians. Do not use techniques that discourage pedestrian activity and destroy or limit the street’s economic functions and social activity.

Foster a safety culture. Publicize and regulate the speed limit with signage, markings, and public information campaigns, and routinely enforce the speed limit. Full-time electronic enforcement by radar-enabled license plate readers or speed cameras and moderate fines are more effective and equitable than manual enforcement with high fines.

Footnotes

1. “Pedestrian Safety Review: Risk Factors and Countermeasures,” (Salt Lake City: Department of City and Metropolitan Planning, University of Utah, School of Public Health and Community Development, Maseno University, 2012)

2. A. Bartmann, W. Spijkers and M. Hess, “Street Environment, Driving Speed and Field of Vision,” Vision in Vehicles III (1991). W. A. Leaf and David F. Preusser, Literature review on vehicle travel speeds and pedestrian injuries (Washington, D.C: US Department of Transportation, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 1999).

3. World Health Organization. World Report on road traffic injury prevention. (Geneva: WHO, 2004).

Adapted by Global Street Design Guide published by Island Press.

Next Section —